Changes in cravings, hunger and diet during the menstrual cycle

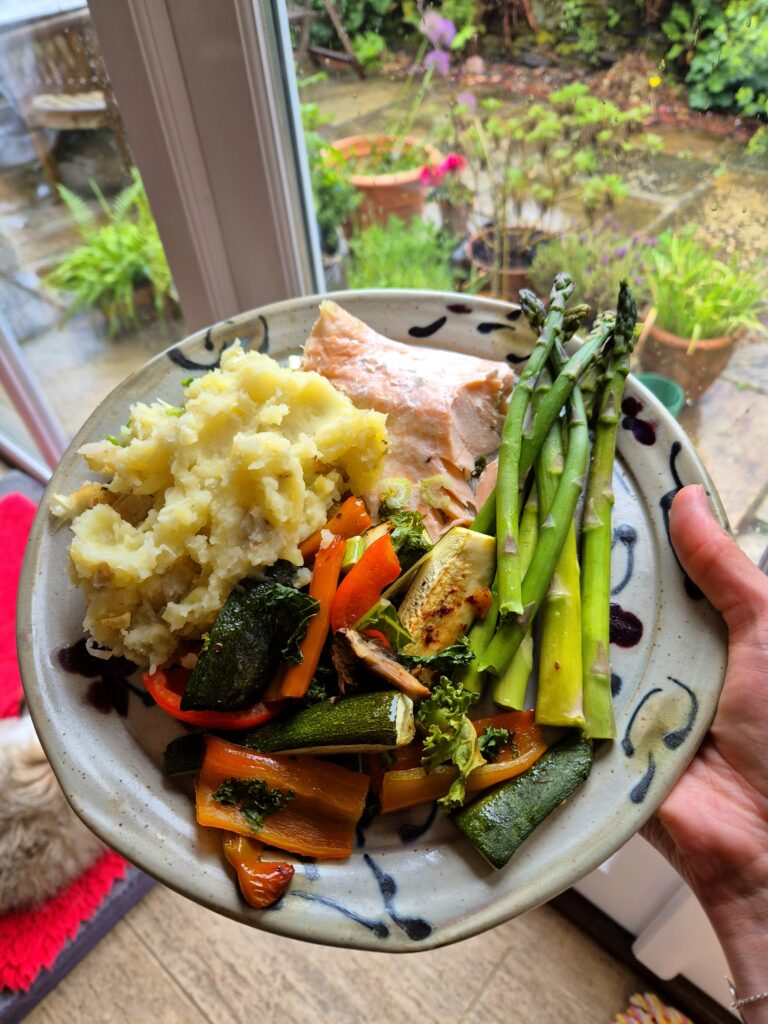

Changes in cravings, hunger and diet during the menstrual cycle Introduction Many women experience changes in appetite and cravings at different parts of their cycle, but why is this? This blog will explore hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle and their impact on your appetite, cravings and dietary intake, and how this change is based on where you are in your menstrual cycle. Read until the end for some tips to improve your dietary habits during your cycle. What phases are there in the menstrual cycle? (Image, Clue, 2019) The menstrual cycle starts on the first day of your period and ends the day before your next period begins. There are different phases in the menstrual cycle; follicular phase (days 1-14) and luteal phase (days 14-28). Our hormone levels fluctuate throughout our cycle therefore potentially having an effect on our diet, mood, digestion, libido, skin, headaches etc. Please note: a cycle from 21-35 days is considered normal 1) Menstrual phase – also known as your period At the end of your cycle and at the start of menstruation, estrogen and progesterone levels drop. During this phase you may experience symptoms such as abdominal muscle cramping, mood swings, and tiredness. Changes to cravings, hunger and diet in the menstrual phase: Cravings: You may experience an increase in cravings for sugary or fatty foods. This is because when estrogen drops, serotonin also drops, which may increase the want for comfort foods, to raise serotonin temporarily (Dye and Blundell, 1997). Hunger: Your hunger may decrease slightly. This is because progesterone and estrogen have lowered appetite as the body is more sensitive to leptin, the hormone which makes you feel full (Hirschberg, 2012). Diet: See recipes here 2) Follicular phase – the first day of your period to ovulation, it overlaps with the menstrual phase During this phase, there is a surge in estrogen, to prepare the body for a potential pregnancy. The symptoms will overlap with the menstrual phase and should reduce when the menstruation finishes, leaving you with more energy and improved mood. Changes to cravings, hunger and diet in the follicular phase Cravings and Hunger: After menstruation, cravings and hunger also reduce due to rising and lowering estrogen levels and low progesterone levels (Hirschberg, 2012). Additionally, leptin sensitivity increases, reducing hunger; this also increases serotonin, reducing cravings and emotional eating (Dye and Blundell, 1997) (Klump et al., 2014). Diet: Continue eating a varied and balanced diet including: 3) Ovulation phase – the period of your cycle where you are fertile During this phase, there is a rise in leuitenising hormone (LH), triggering an egg to be released and a slightly raised temperature. After ovulation, estrogen drops. Some women experience symptoms, such as mild abdominal cramping and mood changes. Changes to cravings, hunger and diet in the ovulation phase Cravings and Hunger: When estrogen is at its highest, before ovulation, leptin sensitivity is enhanced, so there is less hunger, fewer cravings for sugary or fatty foods, so better food choices are likely. However, after ovulation, the opposite happens as estrogen falls, leading to more hunger and cravings (Dye and Blundell, 1997) (Klump et al., 2014). Diet: Intake at the start of the ovulation phase may be lower than the end of the ovulation phase, depending on when the egg is released during the phase. 4) Luteal phase During this phase, progesterone and estrogen increase again, if pregnancy does not occur, these fall again. Additionally, you may experience pre-menstrual symptoms (PMS), which causes symptoms such as bloating, mood changes, changes in food cravings and you may have trouble sleeping. This is caused by the fall in hormones (Watson, 2018). Changes to cravings, hunger and diet in the luteal phase Cravings and hunger: As progesterone and estrogen increase, hunger and cravings increase (Dye and Blundell, 1997). Progesterone is highest before our period. Diet: Due to higher cravings and hunger you are more likely to increase your food intake. This was shown in a study, where they found that women consume 180 kcal more during their luteal phase, in comparison to their follicular phase (Rogan and Black, 2022) Did you know? It is thought that over 90% of women experience at least one premenstrual symptom, and around 48% of people experience PMS (NICE, 2024). This is why it is vital that we understand the impact these symptoms have on our diet and learn ways to work with it, not against it! There is a higher desire for caloric foods, foods high in fats, sugar and salt during the luteal phase compared to the follicular phase. However, the total intake of calories, macro and micronutrients didn’t fluctuate (Souza et al., 2018). Current studies do not consider psychological factors enough. You may notice changes to your cravings, hunger and diet due to symptoms, in addition to hormonal changes. For example, abdominal cramping during your period may suppress your appetite or women who experience PMS may experience increased consumption of comfort foods when they experience mood changes (emotional eating). Does this change throughout my life? From when you first start your periods, also known as the menarche, to when your periods stop, also known as the menopause, your periods may change, and so may your cravings, hunger and diet. This is due to changing hormones during your fertile years heading towards perimenopause. However, your cycles may also change when you are postpartum or breastfeeding! Did you know? Around ovulation, women are more likely to choose new food options. Women, earlier or later in their cycle, are less likely to explore new foods and stick with known options or comfort foods (Nijboer et al., 2024). This has also been found in animals and is linked to changes in higher estrogen levels around ovulation. As more research is carried out, we will gain more evidence to explain why this is happening! What can you do? You can track what phase of your menstrual cycle you are in by using a tracking app, tracking your temperature or manually recording using

Changes in cravings, hunger and diet during the menstrual cycle Read More »